Winter weather and drainage

Related Articles

Amid pressure for the course to remain open at all times, how much does the winter weather of frost, rain, floods and snow affect golf greens’ drainage? Turfgrass agronomist Paul Woodham investigates.

Good drainage potential is a cornerstone of a good golf green, especially if we are looking to achieve year-round performance and playability. Maintaining play and healthy greens is an unsustainable challenge if the profiles are staying too wet for too long. Unfortunately for many, the weather patterns over recent years have created conditions where soil-based greens without a formal drainage system are simply not coping.

Dealing with winter conditions is never easy. At one point last winter, courses in the north west had experienced 75 per cent rain days in the six months since July 2017 and some recorded over two metres of rain in the previous year. It is difficult to say what the trend will be during climate change but the knock-on effect of greens staying too wet will most certainly create problems.

There is a demand for keeping play on main greens during winter months and keeping the course open. This is generally financially driven and golf clubs will not be profitable when closed or unsuccessfully trying to retain members who are dissatisfied with poor greens. There is also the pressure of clubs asking greenkeepers not to disturb the putting surfaces, especially if the greens have barely limped through the winter or suffered during wet autumn conditions. Perhaps this is where the problem of reduced drainage potential started?

The problem of soft and poor performing putting surfaces linked to the accumulation of excess organic matter has been well documented. Quite rightly, greenkeepers have maintained a focus on reducing organic matter to firm surfaces and improve playability, also creating conditions which will favour the development of fine grasses.

Many of the cultural operations to reduce organic matter can be done relatively discretely with modern equipment. Operations such as micro-hollow coring, traditional coring, sand injected scarification or routine aeration and sand integration fit neatly into renovation windows and general maintenance.

Combine this with good control of nutrition and appropriate use of irrigation, and many will have a winning formula for agronomic maintenance of the upper profile. What is frequently forgotten or ignored is the need for deep aeration into compacted or interpacked soils. We are seeing putting greens softening down too easily where excess organic matter holds moisture high in the profile, but the problem often starts deeper down.

Some of my most interesting ‘STRI Programme’ visits are carried out during the winter months. There is little merit taking the stimpmeter or ‘Trueness Meter’ out in the depths of winter but measuring firmness in relation to winter moisture levels is a necessary objective measurement. We will often measure the greens’ performance at their best in summer conditions, but we also need to see them during the period when they are challenged by the pressures of winter play, checking the integrity of the green construction.

Measuring the infiltration of a putting surface is often a wake-up call. Six double ring infiltrometers are placed across a green to measure mm/hr infiltration. The results are typically disappointing on soil-based greens and prove the need to act. Whilst we would strive for an infiltration rate of 20mm/hr, a minimum threshold of >10mm/hr is more realistic.

Unfortunately, we rarely see even this and measurements between 1-3mm/hr are commonplace. The question is whether surface infiltration is being slowed due to the influence of organic matter, soil texture interfaces (change in dressing materials) or the interface where the years of dressing layers are interpacking with the original construction ameliorated topsoil rootzone.

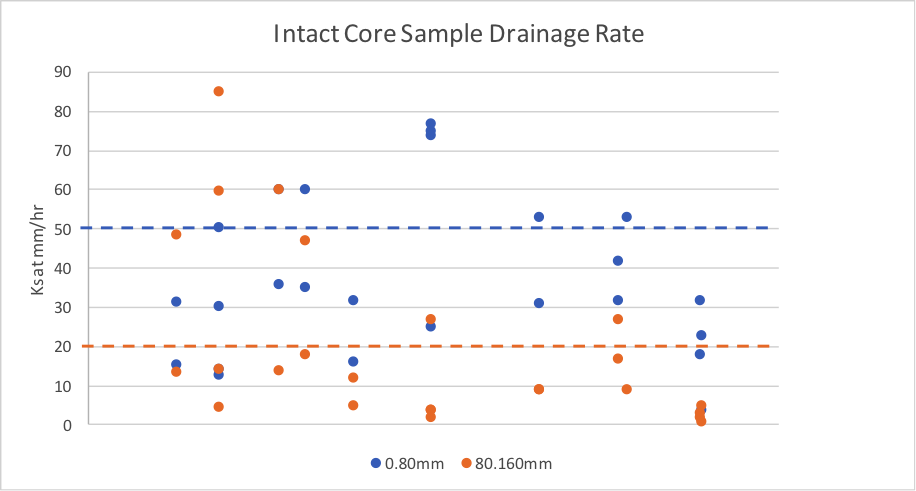

In recent months I have started to replace the infiltrometer assessments with intact core sampling to measure a hydraulic conductivity rate through 0-80mm depth (the zone of organic matter and soil texture changes) and deeper at 80-160mm (entering the native soils and interface with subsoils). On occasion, deeper sampling 160-240mm is taken. The benefit of this test is that it is effectively taking your soil structure intact to the laboratory as the core samples are extracted and retained within sleeves, therefore the drainage rate measured will be the drainage rate potential through the green profile in situ.

The green average results are detailed in the image and we can see that there is a wide variance as suspected.

- 0-80mm depth samples averaged 36mm/hr (range 4-60) whereas 80 160mm depth averaged 1-60mm/hr

- A threshold of >50mm/hr is set for 0-80mm depth and >25mm/hr set for 80 160mm depth

- 68% of greens measured <50mm/hr at 0-80mm depth

- 72% of green measured <25mm/hr at 80 160mm depth

- 48% of greens measured <10mm/hr at 80 160mm depth

- 36% of 80-160mm depth samples failed to drain at >5mm/hr

- Several samples recorded 0-1mm/hr during the measured time but finally drained after 24 hours.

The evidence overwhelmingly suggests that soil-based greens are struggling to cope with the weather and playability demands, especially in wetter locations in the UK. Reducing organic matter will improve the situation in the upper profile but not at depth, and is the cause of organic matter not due to the conditions below?

Can drainage rates be improved by increasing the frequency and effectiveness of deep aeration? Yes, but can this be done whilst finding a balance keeping the greens playable for the club? Some tools allow deep aeration to continue without softening or overly disturbing the putting surface, but the need to deep solid tine must remain and be carefully scheduled at times when the soils are receptive to treatments and are not too wet.

In practicality, if soils are compacting and failing to drain then is aeration alone going to resolve the issue? Probably not, but we can measure progress and the impact of increased cultural maintenance to determine the need for installing drainage.

At a time when there is an increasing need to demonstrate sustainability due to recent withdrawals of some key chemicals, the requirement to create the conditions favouring fine grass species is never more important.

It has been more than 10 years since The Disturbance Theory was first published. Remember that it is called ‘The Disturbance Theory’ not ‘The No Disturbance Theory’. Failing to deal with ‘Phase 1’ to improve drainage is a major flaw, restricting progress towards improvement and, as we see in drainage rate sample results, a decreasing spiral of decline during winter months for many.

The time to disturb is now.

Paul Woodham is the agronomy services manager at the STRI