How to control grass growth on a golf green

Related Articles

Mowing is fundamental in maintaining perfect playing qualities across all natural sports’ surfaces. However, controlling the rate of grass growth and recovery is very much dependent on the surface and sport. Paul Woodham investigates golf greens and how environmental conditions influence growth and performance

A with all sports, golf greens require growth to aid recovery and refine playing qualities. However, if too much growth is stimulated, we run the risk of organic matter accumulation, known as thatch. Playing quality issues relating to thatch build up (surface softness, disease) are well documented. Too much growth also detracts from green speed, especially in terms of am / pm consistency. Think of the greens’ sward as a crop. We are only trying to maintain growth at around 20 per cent of its growing potential. Any more is excess to requirements and will not provide the surface qualities we are striving for.

There are so many factors which influence growth. The fertiliser type / nutrient form will certainly be a factor with differing results seen at various times of year and ground conditions (moisture and temperature). Carefully selecting the appropriate nitrogen form is important, especially if we want the best results at the start and tail end of the growing season.

Up to 50 per cent of the plant’s nitrogen requirements are freely available, more notably in soil-based greens, through mineralisation of organic matter and nutrient delivered from rainfall events and irrigation water. We only need fertiliser inputs to fill in the blanks when we need to augment naturally occurring growth at different times of the year.

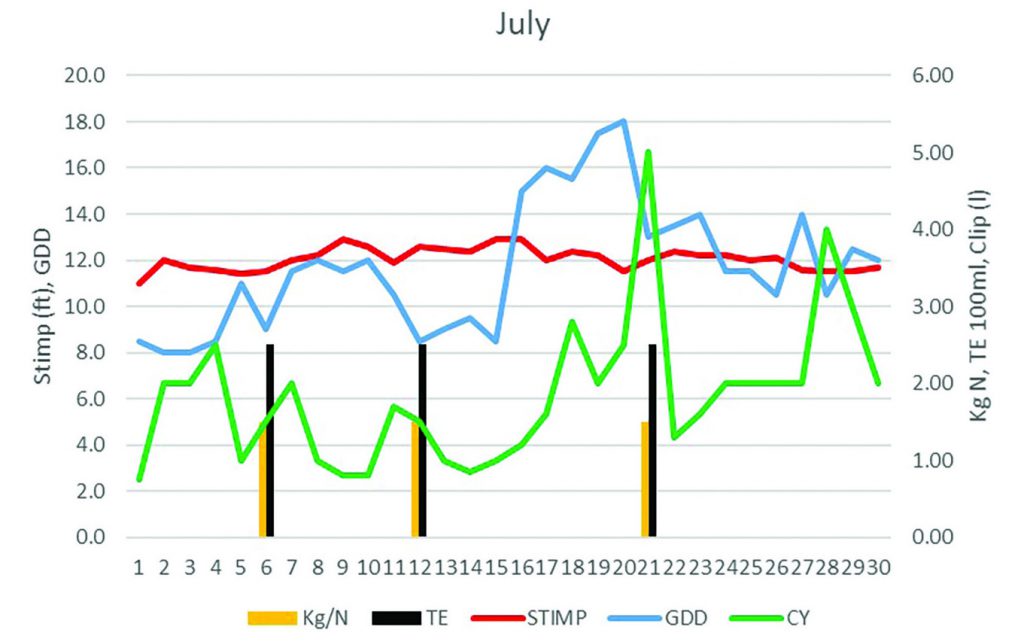

Weather conditions hold the trump card and will combine with geographical and environmental influences to determine growth potential (GP). The topic of GP has been discussed recently by Conor Nolan in GreenKeeping. Conor summarised the situation stating that whilst GP based purely on temperature data has some potential, the missing link is the wind chill and soil moisture influences. The same can be said for Growing Degree Day (GDD) models commonly used to inform Plant Growth Regulator application schedules. GDD is a useful temperature based calculation, especially when growth conditions become more stable, and one which is likely to indicate the need for a narrower gap between treatments rather than monthly applications. Research has indicated that growth control achieved by trinexapac-ethyl is more effective based on frequency rather than the rate of application, but again we are missing the influence of the other key drivers: soil moisture and light.

Measuring and analysing growth

Is it possible to measure and record growth (clip yield) and use the results to direct or confirm maintenance practices such as fertilising and / or mowing adjustments? The answer is YES, and all greenkeepers do this by simply asking ‘how much growth was collected in the grass boxes today?’ or in simple terms ‘how many empties did we do?’ The problem is gathering this information with accuracy. John could be emptying half-full boxes whereas Jane could be emptying when the boxes are full.

Recording measurements of clip yield is easy and not as time consuming as one would think.

Clip yield volume will vary according to all environmental conditions, including soil moisture and light, as discussed and also through any changes to cultural maintenance, that is, brushing, grooming and so on. All of these factors can be recorded and results evaluated when analysing the results.

The challenge is to reveal the influence of inputs (rainfall, irrigation, nutrition, PGRs) and use sward refinement options to control the output of greens’ performance (growth, speed, smoothness, trueness and firmness).

I would expect that over time you will see that moisture and temperature drives growth more than you’d imagine. The information will also help you to revise the timing of nutrient, PGR and sward refinement strategies. The ultimate goal is to save time and money, optimising inputs for maximum output. Can you measure up and improve performance?

Paul Woodham is the agronomy services manager at the STRI