Best management practices to suppress anthracnose

Related Articles

Anthracnose is one of the biggest issues in greenkeeping and can be difficult to control, especially without fungicides. Here, Dr John Dempsey argues that a preventative strategy of reducing turfgrass stress will make it significantly less likely that your course will be hit by it.

Anthracnose is a major problem for many turfgrass managers, particularly during the summer period, worldwide. Like many turfgrass diseases, its causal agent is a fungal pathogen, in this case Colletotrichum cereale. Anthracnose affects mostly cool season turfgrass, with Poa annua being very susceptible. It affects turfgrass in two forms: Basal rot, which as you would expect from the name, affects the lower parts of the turfgrass plant; crowns, stem bases and roots. Foliar blight is the second, and probably the more common form, in which leaves and shoots discolour, having a similar appearance to drought stress in appearance. Whichever form it is, it’s important to note that anthracnose is very much a stress-related disease.

Fungicide treatments can be utilised to suppress this disease, but what I want to highlight today are the numerous management practices that can be employed to alleviate the problem when fungicides are not available or not a desirable option.

There is numerous data available on best management practices to reduce anthracnose incidence, much of it from extensive research carried out at Rutgers University in New Jersey, USA.

As it is stress related, any means of reducing stress will contribute to less disease – pretty much ‘Greenkeeping 101’. For example, turf managers can employ cultural practices which will have a significant impact on disease incidence. A programme which includes regular lightweight rolling, sequential light topdressing, raising the height of cut and judicious use of irrigation inputs have been shown to significantly reduce anthracnose levels.

How does this work? Well increased height of cut equals less plant stress, which equals less disease and, taken in conjunction with regular rolling, greens speed and playability, will be maintained at an acceptable level. But rolling also has supporting data showing it to have a direct suppressive action on many turf diseases, including anthracnose. Regular light sand topdressing will protect the crowns of the turfgrasses, which equals less stress, which equals less disease. Maintaining soil moisture levels at, for example 80 percent evapotranspiration (ET) compared to 40 percent ET, will also contribute to less anthracnose.

Nutritional programmes can also play a significant role in reducing anthracnose. Spoon feeding nitrogen, for example 0.1 lb/M weekly, during periods of high anthracnose pressure, will reduce disease levels, as will maintaining adequate potassium levels greater than 35 ppm (parts per million). But it’s when you start combining numerous elements together in a nutritional program that you will see excellent disease suppression.

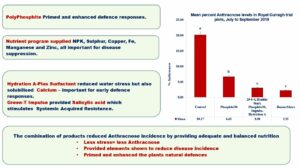

A trial I carried out in 2018 included a programme which included NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium), sulphur, copper, phosphite, manganese, zinc, silica and salicylic acid, apart from enhancing turfgrass quality compared to controls, led to a significant suppression of anthracnose, to a level statistically the same as a bi-weekly fungicide treatment! A similar study running at Rutgers produced the same results.

Anthracnose can be a devastating disease on many fine turf surfaces, but in the absence of fungicides it is possible to contain the problem and reduce disease levels significantly. While all the above cultural and nutritional inputs on their own will have some effect on reducing disease, it’s only when you combine them into a regular maintenance package that you will benefit from the full effects. Think of them like pieces of a jigsaw, it’s only when you start combining them that you will get the full picture.

Dr John Dempsey PhD was course manager at Royal Curragh Golf Club, Ireland’s oldest golf club, from 1993 to 2019. He has a first class honours degree in turfgrass science from Myerscough College and a PhD in turfgrass pathology at the University of the West of England’s Centre for Research in Biosciences