How Notts Golf Club improved its heathland offering

Related Articles

Ten years ago a Nottinghamshire club embarked on a major change to conservation greenkeeping with a reduction in chemical inputs and a regeneration of fine turf, giving firm, fast-running heathland surfaces. Today the venue is considered better than it has ever been, writes Lorne Smith of FineGolf.

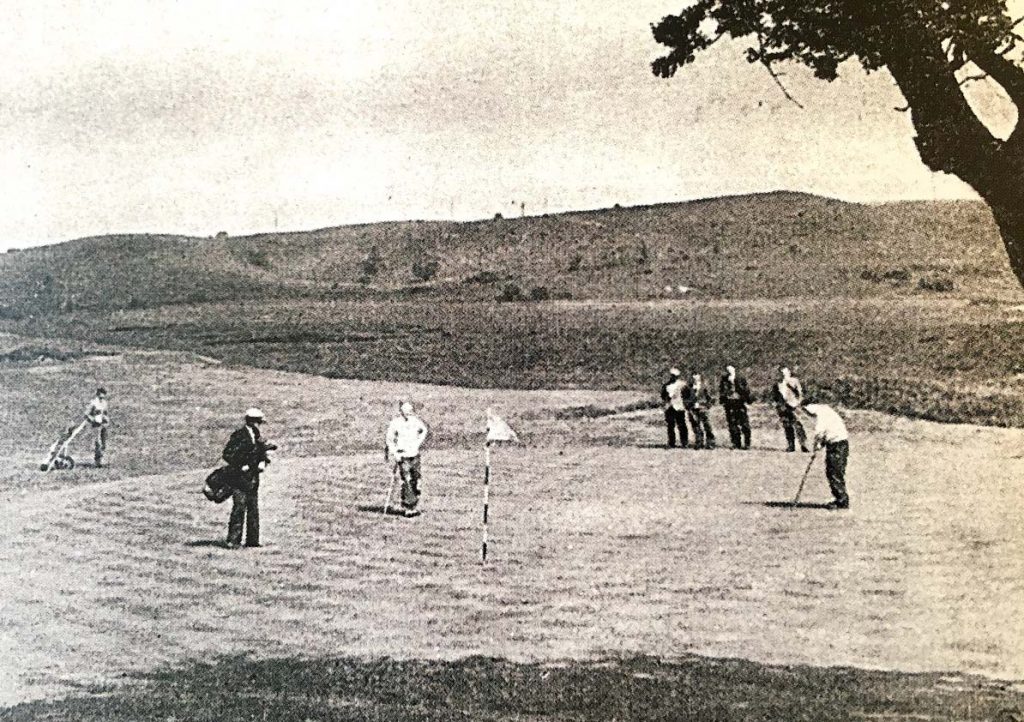

1906. The present 15th green with a sole tree.

How has Notts Golf Club, more commonly referred to simply as Hollinwell, achieved its steady climb in course rankings, to return to the upper echelons of golf, and now be widely considered as one of the finest inland course in Great Britain and Ireland?

The answer is because it has implemented:

- Conservation greenkeeping,

- A regeneration of a heathland environment and

- The recreation of running-golf on firm, fine grass turf.

This is the remarkable story about the triumph and tribulations encountered as the club has broken through to the sunny uplands of the golf world, including being an Open Championship Final Qualifying venue, hosting the Brabazon Trophy for the fifth time, and a likely Walker Cup venue.

Hollinwell, like Ganton, even though they are inland and their sites have for two millenia been open heathland, are similar to seaside links in being blessed with having a few inches of humus lying above sand. This profile provides well-draining poor soil on which wiry, deep-rooting, perennial grasses, those that are the most enjoyable for golf, love to grow.

This site also has the design advantage of considerable movement in the height of the land within the delightful contours that weave through the ancient Sherwood Forest.

The late Dr Ian McLachlan was the original driving force behind returning the course from what had become an almost parkland style, back to its original state of fast running heathland.

The 18th during the 2017 Open Championship Final Qualifying

As at many other courses, nobody realised that a slow invasion of self-set trees had occurred during the late 20th century, which was in addition to the planting of 1,100 trees gifted to the Duke of Devonshire – a Notts GC member – by the Duke of Sutherland in 1938. This led to a reduction of light and air, creating poor growth in the fairways and greens and causing an increase in the proportion of annual meadow weed grass (Poa annua).

In addition, mistakes were made with excessively-fine top-dressing reducing the greens’ drainage, the use of peat on the fairways and the spreading of manure, all of which resulted in softer annual meadow weed grass greens and lusher fairways, limiting the running game so characteristic of its heathland heritage.

The club leadership came to recognise that there were two requirements fundamental to successful change:

- To retain the correct technical advice

- To communicate with, educate and gain support from the membership for a vision that would take a number of years to achieve.

Therefore in 2010 Gordon Irvine MG was retained, following his success at other clubs in working with greenkeeping teams to implement a fine grasses regime, using the Jim Arthur approach.

Phil Stain, the course manager with 20 years’ experience at Hollinwell, became committed to the new non-chemical, simple programme of rigorous aeration, monitoring and lowering humidity, overseeding fine grasses and top-dressing with 80/20 sand / fendress, while slow release organic products like hoof and horn replaced the use of inorganic salt-based fertilisers.

The British weather is ever-changing, and this creates the most difficult aspect of British greenkeeping. Not only does it give a cool season climate that the best golf grasses, the fescues (festuca rubra) and browntop bents (agrostis tenuis), appreciate, but it has also always brought very challenging periods of drought and heavy precipitation to disrupt the best laid plans.

1959. The third green

Membership communication

The club invited Gordon Irvine to give talks to the members in the evening with a clear vision for the future, allowing open questions met with straightforward answers.

From a somewhat sceptical beginning, as the course improved with the best greens becoming smoother and truer, the struggle to convince became easier. Gradually a core group of members grew who understood what and why change was needed.

They naturally spread the word and when greenkeeping setbacks inevitably happened, the programme was not reconsidered but was seen as needing to be accelerated.

Behind all of this change was a club leadership composed of a secretary, chair of green, finance controller and several captains that maintained a consistent approach across the last ten years, giving the greenkeeping team the ability to ride out the lows while measuring objectively the increasing quality and performance of the course.

Let’s now consider the details of the change;

- the increase in fine perennial grasses,

- the removal of trees,

- the limiting of gorse and the increase in heather.

1930s aerial photo of, apart from the central area, an almost treeless course.

Fine grass growth

It is a major problem for greenkeepers when their members become infected with Augusta Syndrome Disease (ASD) and only judge the quality of greens by how fast they run rather than their smoothness and trueness of putt. This creates pressure to shave the grass below 3mm, a height at which only annual meadow weed grass (Poa annua) will survive, in tandem with chemical greenkeeping and its high inputs of expensive fertiliser, fungicides and excess water, all creating softness and target-golf conditions.

The lowest Stain cuts the greens is 4mm and he raises the cut both in winter and in summer dryness if the Greenstester speed of putt threatens to rise above the normal, ideal nine to ten feet range.

The gradual increase in fine perennial grasses has improved putting performance and increased firmness, not only on greens but also gives a more consistent ‘bump-and-run’ bounce on the aprons and run-offs, these being now cut low at between 6mm and 8mm, supplying another integral part of setting up the course for the running game.

A course maintenance week was regularly set aside in the diary and was not ‘bounced’ by other bookings.

It may seem ironic that one of the first measures that Gordon Irvine insisted on was renewal of the greens irrigation system, as at the same time he asked for careful monitoring of moisture levels to keep humidity well below 20 percent. The reason was that the old watering system was uneven and resulted in some areas being over-watered whilst other areas were under-supplied.

An added and incidental benefit of the Jim Arthur programme has been the reduction in the use of high cost chemicals like fertilisers and fungicides and the use of less water, thereby helping the club to fit with a wider society wish to conserve the environment and ‘save the planet’.

New ragged edge natural bunking at Hollinwell.

Tree removal

Since 2000 the club has been working hard to restore the heathland setting and this has meant removing many of the trees on the course, while still retaining some on the periphery and in certain selected spots as part of the heathland mosaic.

All tree removal has been conducted under the direction of the Woodland Trust and Sherwood Forest Trust which actively promotes heathland restoration in North Nottinghamshire along with tree planting in other areas.

Before 1919 the term ‘forest’ did not equate to densely packed trees. It came to typify the results of the Forestry Commission planting vast swathes of conifers, which are incidentally poor for plant and animal diversity. Before then the term forest meant open spaces between areas of woodland where hunting and grazing by deer, sheep and rabbits took place, helping fine grasses and heather survive.

A band of members now regularly go out and pull up saplings from the roughs. Nevertheless, one can perhaps understand how some members, bombarded by the BBC and Extinction Rebellion’s talk of ‘emergency climate change’, might find it difficult to reconcile to tree removal on their golf course. It is a significant task to explain the conservation and golfing enjoyment reasons behind managed heathland restoration.

A cleared area between the fifth green and the 16th fairway in 2020

Gorse control

Various varieties of gorse flower, in early spring and autumn, add glowing yellow hues to brighten up dull days. However, gorse is not only very invasive, but it binds nitrogen and enriches the soil so that even when it is removed the area continues to favour broad leaved grasses such as Yorkshire Fog. The topsoil where gorse grew, along with its roots, needs to be removed if there is any chance of controlling its expansion.

Alistair Mackenzie, one of the most well-respected of golf course architects, said “Gorse and water share the disadvantage that it is practically impossible to play out of them and they are a frequent cause of lost balls. It would appear, therefore, that they should not be used to any great extent as hazards.” However, gorse does support a lot of wildlife including many bird species, but it is best to control its inexorable advance.

Heather also hates being fertilised so removal of gorse and deciduous trees whose leaves in the autumn mulch down under the heather has helped the healthy heather.

Environmental testimonials

Sherwood Forest Trust has on its website: ‘Huge areas of semi-natural habitat – primarily heathland and acid grassland – have been lost over the last few centuries, ploughed up for farmland, planted with conifer trees or consumed by expanding towns. They (Hollinwell) are overseeing a return to heathland with the removal of trees and control of gorse.’

Martin Ebert, the international golf course architect, has recommended the removal of areas of self-set trees and gorse that have surreptitiously invaded areas of play. He has also commended Phil Stain on the heathland style of his bunker work that fits naturally into the landscape.

Ecologist Bob Taylor, on behalf of The R&A, wrote, when he awarded Hollinwell the GEO certification: ‘Notts Golf Club is one of the premier nature conservation sites within the UK and is a prime exemplar and ambassador for best conservation management practice.’

In summary, this has not been a speedy or easy journey, but it is not rocket science.

The most vital aspect in applying the strategy is the need for a vision that is clearly communicated. Most of the members are with the club leadership and the change is today well on its way.

The benefits of conservation greenkeeping are starting to be seen in the extra enjoyment the running game gives to members and visitors and this is naturally being reflected in the club’s rise to the upper echelons of Great Britain and Ireland’s golf course rankings.

For further information, read John Nicholson’s FineGolf articles, ‘Trees on golf courses and ‘Gorse: friend or foe?’

This article was written by Lorne Smith and first published by www.FineGolf.co.uk, a website campaigning for ‘running-golf’ and conservation greenkeeping in contrast to ‘target-golf’ and chemical greenkeeping. There are now over 9,000 golfers who subscribe to FineGolf’s bi-monthly newsletter